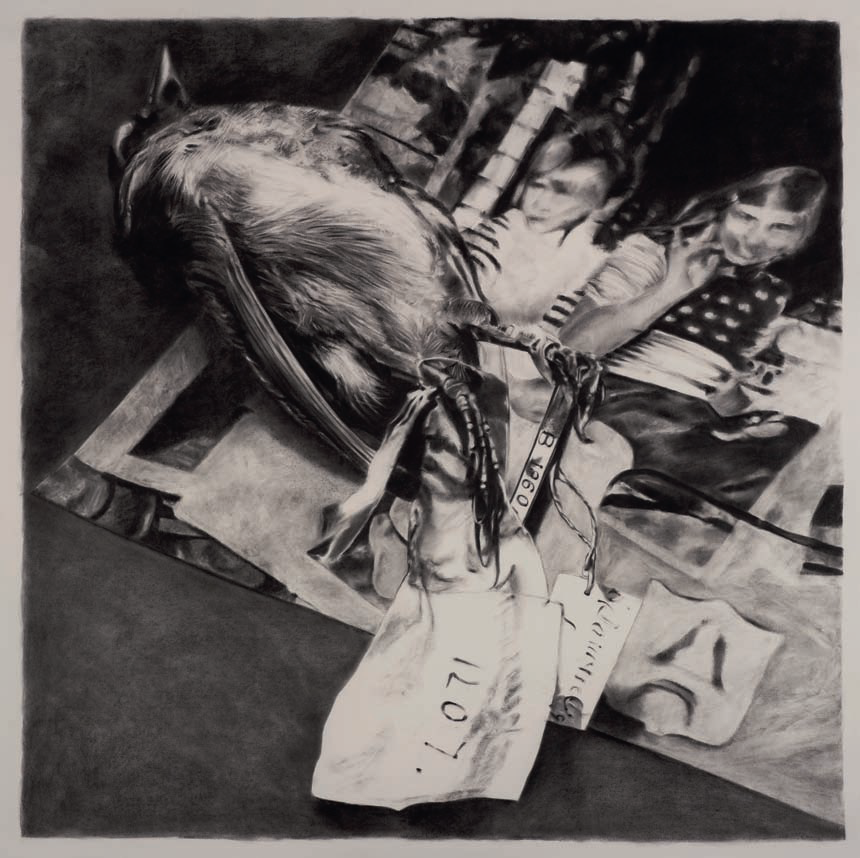

In a small side gallery on the upper level of Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), there is a large graphite-on-paper drawing entitled Darwin’s Girls. It shows a dead finch, with a tag around each leg, lying on a snapshot of two pretty young girls on holiday. The work is not by Damien Hirst, Wim Delvoye, Andres Serrano or even Chris Ofili. It’s a work by Melbourne artist Cassandra Laing, and in many ways it epitomises the collection of David Walsh, the millionaire art collector behind MONA, more than the bold-faced names stirring up the controversy at the recently opened gallery. “I love this,” says Walsh standing in front of it.

The young girls are Laing and her older sister Amanda, who died in 1999 from a brain aneurism after a long battle with breast cancer. The disease also claimed their grandmother’s life. Darwin’s Girls and much of the other work shown in Laing’s 2007 exhibition, It will all end in stars, came after she, too, was diagnosed with breast cancer. And the finch references the birds that played an important role in the development of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Walsh, a vehement atheist with a keen interest in Darwin and evolution, who also lost a brother to cancer, remains deeply moved. “She is tearing apart the reality of her being part of the Darwinian process,” he says. “Her relentless pursuit of an internal truth of something that was real to her, in spite of the fact that this truth gave her no particular comfort. I find that incredible.” Upon seeing the work in 2007, he met with Laing and then invited her to Hobart to see a Darwin letter he had in his collection of original documentation. She didn’t turn up on the appointed day. When they rang her gallery, they found out she had died.

There are deeply personal stories like this behind many of the works at MONA, which is why it is impossible to separate David Walsh the man from his museum. I wanted to focus on the art, to get away from the general myth-making swirling around him. Walsh is fast becoming a character of Tasmanian taxi-driver folklore, the eccentric genius from the wrong side of the Apple Isle who made his fortune through gambling and now lives Randolph Hearst-, or perhaps Howard Hughes-like, in his mansion, running multiple algorithmic online programs, snapping up profane artworks and indulging in all sorts of nefarious pursuits. But Walsh is inescapable. Sometimes literally, given he is said to consider the museum almost an extension of his living room and is often seen marching through or reclining at the bar with his iPad. But also metaphorically, as David Walsh is in every inch of this museum.

It was Walsh who had the grand idea, who bought the Moorilla estate with its heritage-protected Roy Grounds-designed house overlooking the Derwent River in 1995 as a site, who sank $100 million dollars of his fortune into the museum’s construction. He decided it should be underground, with no natural lighting and with dark walls. He dispensed with the white labels conventionally fixed next to each work, instead providing visitors with the O, an iPod-like device he conceived that offers up background information on the works on either a basic, intellectual or “gonzo” level. And it is his idiosyncratic philosophies that informed the purchase of every piece in his $100 million, 2,000-strong portfolio.

Photography by Earl Carter

Much has been made of the overarching sex and death themes of his collection, and on first tour, the opening exhibition MONANISM is as disconcerting as promised. From the ashes of Walsh’s father interred in a Fabergé egg-like work by Julia deVille, the enormous gaping icepick head wound that is Mat Collishaw’s Bullet Hole, the indolent transsexual portrayed by Jenny Saville in Matrix, to the suicide bomber’s remains immortalised in Belgian chocolate by Stephen J Shanabrook in On the Road to Heaven The Highway to Hell. My group, initially somewhat exhilarated by what lay ahead, has quietened. Perhaps they are more sophisticated than I am; perhaps they are taking it less personally; perhaps like a pornography overload, they have become immune.

Still it keeps coming. The 140 vagina plaster casts of Greg Taylor’s Cunts and Other Conversations, the replica human digestive system that is Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional that defecates twice a day, every day. Juan Davila’s explicit portrait of Burke and Wills in The Arse End of the World. Jenny Holzer’s Lustmord tattooed tales of rapists, their victims and those who stood idly by. The junkie paraphernalia in Shanabrook’s The Moth Collection. Gregory Green’s bomb inside a Koran. Everything is up for grabs: even one’s bowel movements, thanks to a surprise mirror installation in the facilities, also known as Gelitin’s Locus Focus.

Photography by Earl Carter

There are undoubtedly some moments of lightness, like the mesmerising information waterfall that is Julius Popp’s Bit.Fall or the sweeping lights of Conrad Shawcross’s beautiful folly Loop System Quintet. The charm of Candice Breitz’s karaoke heads singing Madonna’s entire Immaculate Collection album for Queen (A Portrait of Madonna), or the levity of the obese Porsche that is Erwin Wurm’s Fat Car. And the sweet blessed relief of Wilfredo Prieto’s Untitled (White Library).

Perhaps those who best understand the collection, and therefore Walsh, are those who worked with him on the Herculean task of creating the museum. My next tour guide, Nicole Durling, is an acclaimed artist in her own right. She was working at Sotheby’s as a curator of Australian contemporary art when she first met Walsh. “Not many people hit it off with him, or he didn’t hit it off with many people from either the commercial art or this world, it just wasn’t his bag,” she explains. Late one night in a Melbourne bar, he asked her to come and work for him. “It was very vague. I said: ‘Well, what do you want me to do?’ and he said: ‘Oh, I don’t know, just buy some stuff.’”

She has worked alongside MONA’s other curators, Mark Fraser and Olivier Varenne, since 2007, scouring the art world for works that may appeal to Walsh. Trying to read his mind can be challenging. “Just getting into his head, getting what he will look at, but then we will present something and he’ll go:‘No, that’s rubbish.’”However, he is nothing if not open-minded. “He certainly allowed for a great deal of play and really stupid ideas to be tabled [in the lead-up to the opening], and he would say, that’s a bit of a weird idea [but] see if it’s feasible, see how you go,” she says. “There were a lot of ideas that fell to the wayside and there were also some very stupid ideas that ended up in the museum.” For her, there’s more to the collection than just having a big chequebook to play with. “It’s more about: ‘How does it sit in the collection? How does David interact with it? How does it interact with other works in the collection and can it give that different feel, that different sensation to the experience?’”

She disagrees with the sex and death theme. “That’s such a dumbing down,” she exclaims, “and he did it, he’s the one who dumbed it down. In his mind, it permeates everything we do, seeking one, avoiding the other, that’s what it is to be human. I don’t know if I necessarily agree with that; it’s a little bit reductionist to my mind.”

She points to Fiona Hall’s knitted videotape installation Scar Tissue. When Walsh saw it, he wasn’t particularly interested in the artist or the rationale behind it; he just liked it. Durling, too, doesn’t go digging for meaning, preferring to discover something that is aesthetically engaging, an idea that vibrates on a certain level. “What makes a great work of art – who the hell knows?” she laughs. “And that’s the beauty of it, don’t try to pin it down, don’t try to ask why, don’t try to reason.” She adds: “That’s why I have difficulty with this sex and death [theme], it’s too reductionist – and there’s no beauty in that, there is no mystery.”

There is a great deal of humour in the collection, dark humour, schoolboy humour and plenty of the absurd. We walk past James Angus’s Truck Corridor, a big green Mack truck parked right in the middle of the underground gallery and boxed in with tight white walls. “People have asked: ‘How do you drive it out of here?’ ‘How are you going to get it out?’ ‘Did you build the walls around it?’ We say: ‘Yeah we did,’” laughs Durling. “That’s kind of fun to play around with people’s minds.”

She was involved with the purchase of Arthur Boyd’s stunning Melbourne Burning. “[It was] an amazing experience. It was hanging on the wall in the National Gallery of Victoria and it was just like going shopping at the National Gallery.” The artwork was on longterm loan, but when it came up for sale, Walsh nabbed it. It was never at risk of disappearing from public view, like many works in private collections. “In Europe and America this is the norm, you have a collection, you show it. Here I guess, is it the tall poppy thing? He’s a risk-taker, so that disturbs people a bit. He’s done it, he hasn’t come from anywhere, he hasn’t come from an artistic family or family of collectors, which within Australia is certainly where most arts patrons come from. He’s just this black swan off doing his own thing.”

MONA also has an extensive library, housing Walsh’s collection of books and original documents, including letters from Darwin, Newton and Einstein. “David is an autodidact, so he values books and learning [and] it’s something he’s got a great passion about.” Next to the library is a purpose-built pavilion for Anselm Kiefer’s dramatic steel, lead and glass work Sternenfall. “Maybe David met enough of these artists with very bold ideas and maybe a bit grandiose, and so he decided that he would build a museum to himself,” says Durling.

One of the criticisms levelled at MONA questions whether its curatorial premise is sufficiently robust. Durling disagrees. “Culturally, why we feel rigorous dialogues and academic approaches to exhibition-making should be at the forefront of everything and should be taken above any other reason for putting an exhibition together, I don’t know. I don’t think it should be the only reason why we do things. I don’t think just because it’s intellectually or academically resolved, it doesn’t mean it’s any good. I’m not saying that just because it isn’t academically resolved doesn’t make it any good either,” she says. “I think it’s playing with outcomes. Just seeing if you put these things together like that, what does that look like? Okay, that doesn’t work, how about you put this into it?”

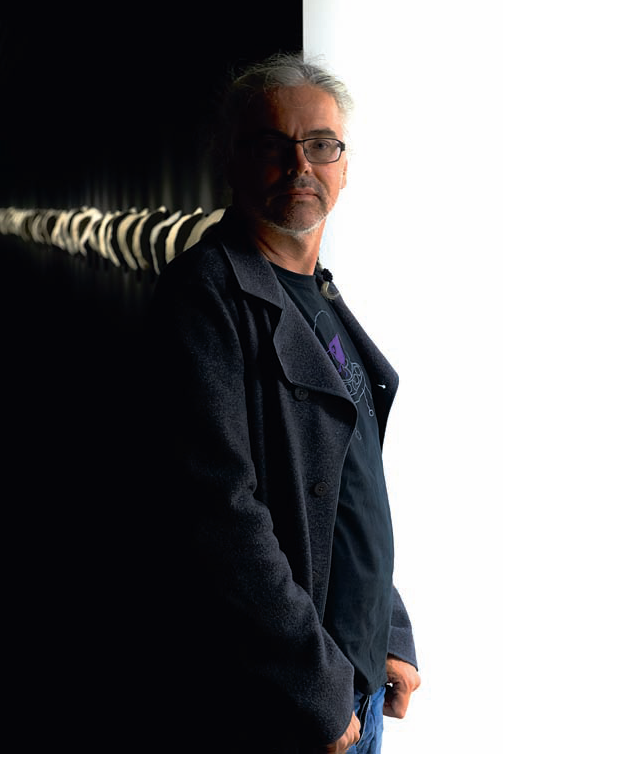

In person, Walsh lives up to the hype very nicely, thank you very much. Slim-set, his boyishly long grey hair divided into two French braids, he walks and talks quickly, spilling historical facts, a few expletives and even an explanation as to why sex is like typing (it’s all about muscle memory, apparently). He is charismatic, outrageously intelligent and apparently unflinchingly honest, but difficult to actually connect with.

“You don’t start collecting art with the view to being an art collector,” he starts. Growing up, he collected coins and spent hours in Tasmania’s Museum and Art Gallery, but it was only when he couldn’t get the profits of a blackjack game out of South Africa that he bought his first artwork, a wooden Nigerian palace door he’d seen in a Johannesburg commercial art gallery. We pass a spectacular display case of antique coins and his delight is obvious. “They are incredibly elegant, they are chunks of history and they remind us that our parochialism is a myth structure that we’ve imposed on ourselves – so I like them,” he says firmly. “I didn’t know this type of thing existed and then I found out that they did and I was amazed.”

Photography by Earl Carter

In his words, he just started buying contemporary art. He wasn’t particularly interested in contemporary art, “it just looked like all other art to me”. His first piece was Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Skin Flint. “I think it’s an incredible work but I don’t think Basquiat was an incredible thinker, and this is seriously shallow. It says something about how art emerges. I have now met a lot of artists and a lot of them aren’t necessarily thinking their way through the world, they are just reacting [and] engaging with whatever it is that they do.”

He chose to display the most interesting pieces in the opening exhibition, and there wasn’t much he hesitated about. “I’m certainly aware that stuff like this has a chance of offending,” he says pointing to Wim Delvoye’s image of Osama bin Laden tattooed onto pigskin, “but [Islam] can’t corner the market in anger or rage. I have every right to make the same sort of arguments but it didn’t really influence my decision about what to put out. Although a few of my staff said: ‘Do we really want to have a go at Islam?’ I said: ‘Why is it any different from anything else?’” He adds: “I just wanted to build a place that didn’t create an academic structure for art that was forbidding [and] difficult to engage with. I wanted to make hard stuff easy.”

We move into a darkened room, stepping across paving stones surrounded by black water to two high rectangular tombs. In one is the 100 BCE Egyptian mummy and coffin of Pausiris, the other an electronically generated image of its twin that slowly reveals its contents. Opposite is Serrano’s disturbing portrait of a recently deceased young woman, The Morgue (Blood Transfusion resulting in AIDS). Disturbed is the required reaction. “When someone has been dead 20 years, we treat them as if they used to be alive, but when they have been dead 200 years, they become an object,” says Walsh, warming to his topic. “At some point between last week and 200 years, death becomes never having been dead – that fascinates me.” He wants people to question the concept of mortality. “We treat mortality as a very shortterm thing. You seem to be dead only about as long as you were alive and then you were never dead … We probably need to do those things, or we choose to do this, because deep time has the capacity to make us realise that we have no relevance whatsoever.” He continues: “We are tiny meaningless things trying to give ourselves meaning. I think it was Voltaire who put it: man created God in his own image.”

On the level below is the large untitled piece by Jannis Kounellis, inspired by Picasso’s Guernica, alternately featuring rope, coal and freshly slaughtered beef carcasses. “This is the serious absence of metaphor,” Walsh gestures, “it’s a structure, the coal, the meat, the rope, the killing – this is what it is to be human.” A long-time vegetarian, Walsh says the confronting work, like Cloaca Professional, Locus Focus or Cunts and Other Conversations, exemplifies his railing against the compartmentalisation of life. “The reality is these are not things that people allow themselves to be aware of in a dayto- day way, so I want people to think about the consequences. If it engages or enrages, that is a good outcome – but funnily enough, it has enraged far less that I expected,” he says, perhaps a little disappointed. “That could be a good thing, it could be that people are thinking about it without floundering or it could be that they are missing the metaphor.”

Photography by Earl Carter

On the opposite wall is Walsh’s favourite piece. The length of an Olympic swimming pool, with 270 panels, Sidney Nolan’s breathtaking Snake is reportedly the largest work ever produced in Australia. Until it was hung at MONA, it had never been seen because no other gallery had the space for it. Walsh constructed a wall specifically for it and it informed the architecture and the logic of the gallery thereafter. Interestingly, it’s about neither sex nor death: it’s about achievement. Here is one man’s incredible talent exemplified and sublimely executed.

For Walsh, it makes him realise that what we do as humans that makes us human is not the conscious things. He sees the work as Nolan developing muscle memory, creating an automatic process that leads him to create more complex images. “I think he was relentlessly exploring the nature of himself,” says Walsh. He points out some of the latter panels, which look like bats. “I don’t know of anyone who relentlessly tore apart what he was thinking, why he was thinking it, and this is very attractive to me. I love him trying to grapple with his own ego, his own recognition.”

As I leave MONA, I sidestep grandmothers and Hells Angels, tourists with cameras and teenage boys skylarking. As an attempt at democratising art, Walsh has already scored, with the museum drawing record crowds. Some visitors will love it. Some will loathe it. Some will assume a studied nonchalance. Regardless, Walsh must be admired for jump-starting a conversation about contemporary art on his own terms. And while some will simply head to his nearby Moo Brewery for a pint of pale ale, others may walk away pondering the ideas he has put forward.

Published in Vogue Australia August 2011